Paris Agreement turns five: It is NOW or NEVER

Five years ago, when physical congregations were possible, the world met in freezing cold Paris to sign the Paris Agreement on climate change. Five years later, the world is still far from meeting climate goals. What is clear is in the past five years, every part of the world has been wrecked by catastrophic weather events. Governments across the planet met on 12th of December 2020 to commemorate the 5thanniversary of the Paris Agreement, where they were invited to present new and ambitious climate commitments.

Five years ago, when physical congregations were possible, the world met in freezing cold Paris to sign the Paris Agreement on climate change. Five years later, the world is still far from meeting the climate goals. What is clear is in past five years, every part of the world has been wreaked by catastrophic weather events. Governments across the planet met on 12th of December 2020 to commemorate the 5thanniversary of the Paris Agreement, where they were invited to present new and ambitious climatecommitments.

Climate change is a reality and we are already seeing the devastating impacts, even as the global temperaturesare rising1.2 degree Celsiuson average since the 1880s - and it is expected to go above 3°C by theend of this century. Today, when the world is locked down because of a raging virus pandemic, it is time to take stock of what was agreed and what needs to be done.

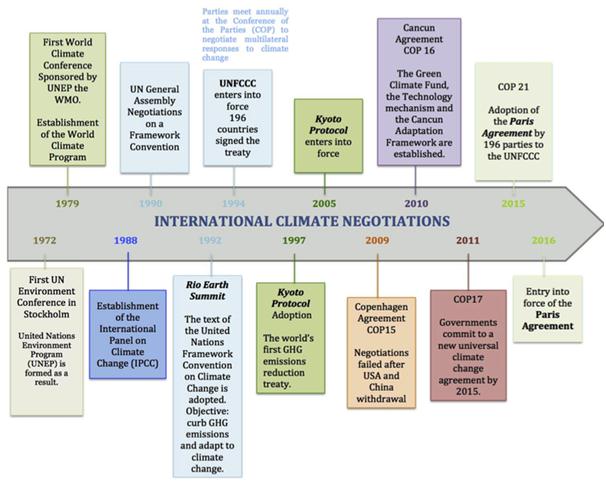

Timeline for International climate negotiations

The Kyoto Protocol

Kyoto Protocol is an international treaty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Kyoto Protocol applies to sixgreenhouse gases - carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons, and sulfur hexafluoride. It is an extension to the 1992 UNFCCC. Kyoto Protocol is based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDRs) keeping in mind the socio-economic development of the concerned countries and the polluter pays principle.

Kyoto Protocol was adopted in Kyoto, Japan on 11 December1997.Itcame into force on 16 February 2005.84 countries are signatories of the Kyoto Protocol. Currently,192 countries are parties of the Kyoto Protocol.Although the 36 developed countries had reduced their emissions, global emissions increased by 32 % from 1990 to 2010. The financial crisis of 2007-08 was one of the major contributors to the reduction in emissions.Canada withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol in 2012.

The detailed rules for implementation adopted at COP-7 in Marrakesh, in 2001 and are referred to as the Marrakesh Accords. Kyoto Protocol is a legally binding agreement. Only members of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) can become parties to the Kyoto Protocol.Kyoto Protocol was adopted at the 3rdsession of UNFCCC. The Official meeting of all countries associated with the Kyoto Protocol is called the Conference of Parties (COP). The agreement has three mechanisms that are means to achieve the Kyoto targets:International Emissions Trading, Clean Development Mechanism, andJoint Implementation.

The Protocol's first commitment period started in 2008 and ended in 2012. Kyoto Protocol Phase-1 gave target of cutting down emissions by 5%.After the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol ended, an amendment i.e. changes to the agreement was carried out at Doha. This amendment, called Doha Amendmentto Kyoto Protocol, talks about emission reduction targets for the second commitment period. The 2ndcommitment period ranges from 2012-2020.India has ratified the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol i.e. meet the emission targets for the time period 2012-2020.Phase-2 gave target of reducing emissions by at least 18% by industrialized countries

India is a non-Annex I country.India was exempted from legally binding commitments on greenhouse gas emissions.India emphasized on the differentiation between developed and developing nations concerning the burden of responsibility for climate action.India successfully defended its obligation on socio-economic development while concurrently forcing developed countries of the Annex I category to take more responsibilities on curtailing greenhouse gas emissions.Since the per capita emission rates are much smaller for developing countries compared to the developed countries, India takes the stand that the major responsibility of reducing emissions lies with the latter.

The Paris Agreement

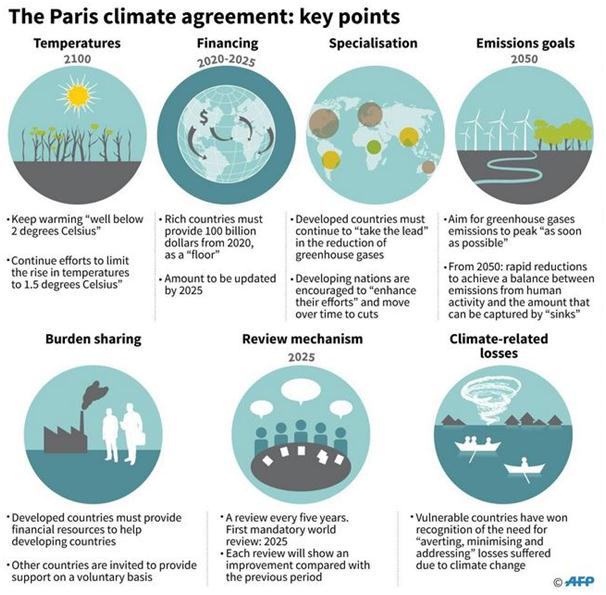

Paris Agreement is a multilateral agreement within the UNFCCC signed to reduce and mitigate the greenhouse gas emissions. The agreement was signed on 22ndApril2016.Currently, 195 UNFCCC members have signed it. The goal of the Paris Agreement is to curtail the rise of global temperature this century below 2-degree Celsius, above pre-industrial levels, and also pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Further, it intends to develop mechanisms to help and support countries that are very vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change. An example would be countries such as the Maldives facing threats due to sea-level rise. Additionally, it confirms the obligation that developed countries have towards developing countries, by providing them financial and technological support.

The agreement talks about 20/20/20 targets, i.e. Reducecarbon dioxide emissions by 20%, Increase the renewable energy market share by 20%, and Increase the energy efficiency by 20%.

There is a major difference between the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. In the Paris agreement, there is no differentiation between the developing and developed countries, whilein the Kyoto Protocol, there was a differentiation between developed and developing countries by clubbing them as Annex 1 countries and non-Annex 1 countries.

The Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)refers to the contributions that need to be done by each country to achieve the overall global goal. Further, the contributions need to be reported every 5 years to UNFCCC. These contributions are not legally binding. Most importantly, the goal is to make sure that all countries have access to technical expertise and financial capability to meet the climate challenges.Interestingly, as per the Paris agreement, Parties have the right to include the reduction of emissions in any other country as their NDC, as per the system of carbon trading and accounting and is called International transfer of Mitigation outcomes.

The developed countries have committed $ 100 Billion a yearof Financial Support which was pledged during the Paris Agreement. The Financial commitment would be balanced between mitigation and adaptation.G7 countries had announced $ 420 Million for Climate Risk Insurance and launching of the Climate Risk and Early Warning Systems (CREWS) initiative. Further, there has been an announcement of $ 3 Billion commitment for Green Climate Fund.

The article 6 of the Paris Agreement help Governments establish and implement the NDCs. Furthermore, it helps in establishing a global price of carbon. The advantage of establishing a global price in Carbon is that if countries exceed their NDC, those countries will have to bear the cost of global warming.

The Paris Agreement 2015 changed the terms of the agreement on climate action fundamentally. However, countries like the United Statesof America, which had been long-term historical contributors, did not want this deal. According to the views of the United States, it puts too much onus on these countries to make reductions. They want to erase the very idea of the past and to focus on the need for all to act and for all to take actions based on what they believed they could do. Accordingly, Paris Agreement succumbed to this idea.In this way all countries threw in their targets into the ring, called the NDCs; and even as Paris Agreement was gravelled down, it was understood that the sum of these NDCs, would add up to at least 3°C temperature increase by century end. But most importantly, hopes were high. The United States, for once had been roped in through this compromise. Further, to keep the temperature rise below 1.5°C it would be mandatory to ‘ratchet’ up the NDCs - based on the fact that countries would realise the imperative of taking more drastic action as climate change impacts hit them.

Criticism and Shortcomings in the Paris Agreement

According to a study published in Nature in 2016, thecurrent pledges by countries are too low to lead to a temperature rise below the Paris Agreement temperature limit of “well below 2°C”, i.e., the NDCs so far submitted will not result in the desired objective of limiting increase of global warming to below 2°C.Even a UNFCCC report had observed that even if all the pledges made by 197 countries that are signatory to the Paris pact were fulfilled, it would be insufficient to meet the conservative goal of keeping global temperature rise within the 2 degree Celsius threshold. Furthermore, most of the agreement consists of “promises” or aims and not firm commitments.The Paris Agreement requires that all countries - rich, poor, developed, and developing - slash greenhouse gas emissions. But no language is included on the commitments the countries should make.Nations can voluntarily set their emissions targets and incur no penalties for falling short of their targets.

The starting point of $100billion per year remains under 8% of worldwide declared military spending each year.There is only a “name and shame” system or a “name and encourage” plan and the ‘contributions’ themselves are not binding as a matter of international law.Since the only mechanism remains voluntary national caps on emissions, without even any guidance on how stringent those caps would need to be, it is hard to be optimistic that these goals are likely to be achieved.

Further, global emissions may have reduced marginally in the past year because of COVID-19, but this slowdown is temporary. The United Nations Environment Programme’s Emissions Gap Report 2020 finds that global GHG emissions have continued to rise in the past three years. In 2019 emissions were a record high. In 2019, the total greenhouse gas emissions, including land-use change reached a new high of 59.1 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent.

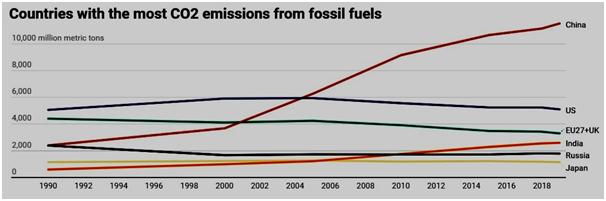

The Emissions Gap Report, 2020 submitted by United Nations Environment Programme has stated that the world is still heading for a temperature rise in excess of 3°C this century – far beyond the Paris Agreement goals of limiting global warming to well below 2°C and pursuing 1.5°C. Global greenhouse gas emissions have grown 1.4% per year since 2010 on average, with a more rapid increase of 2.6% in 2019 due to a large increase in forest fires. G20 countries account for the bulk of the emissions. Over last decade, the four emitters (China, the United States of America, EU27+UK and India) have contributed to 55% of the total GHG emissions. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, carbon dioxide emissions are predicted to fall up to 7% in 2020. However, this dip only translates to a 0.01°C reduction of global warming by 2050.

The emissions by theUS in 2019 were higher than in 2016. This even as the country reduced its energy-related emissions by a whopping 30 per cent in the past decade. Additionally, a temperature rise, even of 1.5°C, may result in catastrophic and irreversible changes.Even a 1°C hotter planet is not a steady state, says a report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

It is also clear that at the current levels of emissions, the world will ‘exhaust’ the carbon budget by 2030 for 1.5°C target. This when large parts of the world, including India, will need the right to develop - which in today’s context where coal and natural gas, both fossil fuels, remain the most competitive fuels, would mean increase in emissions.It is clear that the transformation to new energy systems, driven by renewable, is still a way away. Even in most low-carbon advanced regions like the European Union, coal is still as large a part of the energy system as is the new renewable technology.So, it is necessary to move towards this transformation in the still emerging world, but there are no enabling conditions, that will make this happen.

The Suggestive Way Forward

In order to ensure transparency of efforts, strict obligations should be implemented on all parties, such as having to report - inventories and information on the implementation of NDCs, expert review and multilateral consideration of progress. Implementation is the key for the long-term success of the Paris agreement. The political momentum that was captured in Paris needs to be maintained.

The political will has to stay involved beyond the Paris conference in order to connect the Paris system with the real world and keep the relevant political and financial institutions on track to increase efforts. There is a need forcapacity building for the progressive preparation and technical implementation of NDCs. The ‘intended’ contributions (INDCs) submitted before and in Paris showed a universal engagement by all countries, although their content is not ambitious enough for staying well below 2°C. This political will needs to be under-pinned with the capacity to define and implement actions on the ground. Governments should imbibe possible actions to support and enable lower carbon consumption include replacing domestic short haul flights with rail, incentives and infrastructure to enable cycling and car-sharing, improving energy efficiency of housing and policies to reduce food waste.

The forthcoming negotiationson Paris Agreementshouldfinalise the remaining technical details, in particular with regard to the NDC features and the transparency and they must find out ways to become carbon-negative. These details should provide a counterbalance to the flexibility parties have in defining and implementing their actions. They can ensure public credibility of individual NDCs and actions and thus foster ambitious action by all.

The new buzz-word is ‘net-zero’.Already many countries in the world have declared net-zero targets for 2050. For example,China has said that it will be net-zero by 2060. Now the pressure is on all governments, including India, to set its future target. The problem is not with the ambition or intention to turn net-zero, but the absenceof a plan to get there. Further, apathwaymust be defined that would make greenhouse gas emissions go away. Countries have to come up with hard targets for the coming decades. Global fossil fuel production needs to decline 6 per cent every year for the next decade for a 1.5°C rise in temperatures, according to the United Nations Environment Programme Production Gap Report.

For a 1.5°C pathway, coal output will have to decrease 11 per cent annually through 2030; oil and gas production should fall 4 per cent and 3 per cent, respectively. But countries aim to produce 120 per cent and 50 per cent more fossil fuel by 2030 than would be consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5°C or 2°C, respectively.This translates to a 2 per cent annual average growth in global production over the next decade even as all signs point to a continued global fossil fuel production gap.

Some experts call for the creation of a climate club - an idea championed by economist William Nordhaus - that would penalize countries that do not meet their obligations or do not join. Others propose new treaties that apply to specific emissions or sectors to complement the Paris Agreement.Many cities, companies, and organizations are making plans to lower emissions, heeding the UNFCCC’s call to become climate neutral by the second half of the century.Some have gone further to say they will be carbon negative, removing more carbon from the atmosphere than they release. However, critics have accused some of these companies of greenwashing: marketing themselves as eco-conscious while continuing harmful practices.

In theINDCs declared by India, it has pledged to improve the emissions intensity of its GDP by 33 to 35 per cent by 2030 below 2005 levels. It has also pledged to increase the share of non-fossil fuels-based electricity to 40 per cent by 2030. It has agreed to enhance its forest cover which will absorb 2.5 to 3 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (the main gas responsible for global warming) by 2030.

There has been a rise in extreme weather events due to the on-going climate change. Apart from reducing the greenhouse gas emissions, it is extremely essential to take appropriate actions to minimize the risks associated with extreme weather events. A report by Council on Energy, Environment and Water on the Extreme weather event hotspots recommends that we need to develop a Climate Risk Atlas to map critical vulnerabilities such as coasts, urban heat stress, water stress, and biodiversity collapse. Further, there is a need for development of an Integrated Emergency Surveillance System to facilitate a systematic and sustained response to emergencies. Additionally, we must mainstream risk assessment at all levels, including localised, regional, sectoral, cross-sectoral, macro and micro-climatic level. Correspondingly, countries must enhance the adaptive and resilience capacity to climate-proof lives, livelihoods and investments. Lastly, we need to increase participatory engagement of all stakeholders in risk assessment process.

Conclusion

The former chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate ChangeCountries Sir Robert Watson has stated that there is aneed to double and triple the 2030 reduction commitments to be aligned with the Paris target. We have the technology and the knowledge to make these emissions cuts, but what are missing are strong policies and regulations to make the achievement of goals possible. The Emissions Gap Report has stated that stronger action must include facilitating, encouraging and mandating changes in the consumption behaviour by the private sector and individuals. We need more reality checks in the climate change narrative.The impacts are certain, but as yet, action is pusillanimous.

All countries need to step up, accept that global emissions must reach net zero by 2050 and take very large steps to make it happen. Climate Emergency has been declared in various countries to reduce or halt climate change and avoid irreversible environmental damage. The countries include the UK, Portugal, Canada, France, and Japan. NZ could declare in the near future.Climate change is not the primary priority for most jurisdictions - though it is an existential crisis for some, including some small island states. That needs to be acknowledged and built in to the goals and planning.TheIPCC reporthas acknowledged that the pathways to avoiding an even hotter world would require a swift and complete transformation not just of the global economy but of the society too. This could only be possible if the world rejects nationalism and parochialism and adopts collaborative responses to the crisis.The pandemic has provided an opportunity for a recovery that puts the world on a 2°C pathway and we must learn lessons quickly and effectively to avoid the doom. The bottom line is that the post-COVID recovery needs to focus on low carbon, ideally decarbonisation by moving away from fossil fuels; increasing their short-term NDC enhancements and commitments, by putting money into technological developments; and lastly, implementing additional policies to drive thechanges in technology, operations, fuel use and demand.