EQUALISATION LEVY &DIGITAL SERVICE TAX (DST)

The world at present is moving ahead with a rapid pace of development. Enhanced use of technology and digitalization have touched upon most aspects of this fast journey. The use of internet has highly increased the avenues for doing business by removing the requirements for physical presence in a country for delivery of goods or services.

The world at present is moving ahead with a rapid pace of development. Enhanced use of technology and digitalization have touched upon most aspects of this fast journey. The use of internet has highly increased the avenues for doing business by removing the requirements for physical presence in a country for delivery of goods or services.

This has indeed transformed the global economy. At the same time, it has given rise to several questions related to ‘taxation’ of the consideration/income generated by using the digital platforms for conduct of business. The present global taxation system is based on the traditional ‘brick and mortar’ system of business environment. But the modern business practices based on digital economy have rendered it necessary to find modern solutions for an effective global taxation regime.

What have the been global efforts in this regard?

Several countries have come together at the global level to find a unified solution to the new challenges. The objective of such discussionshas been to develop new standards for offering a global roadmap to governments for collection of tax revenue, and at the same time providing businesses the certainty needed to invest and expand.

The ‘OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS’is one of the most important platforms at present for discussion on norms on global economy. Under this framework, the tax challenges raised by digitalization is currently the top most priority. Discussions have been going on since 2013, but till now no mutually acceptable solution has been found by the participating countries.

What is BEPS?

BEPS expands to Base Erosion and Profit Shifting. BEPS refers to practices of tax planning by multinational enterprises that makes use of gaps in the linkages between different taxation systems. Using these gaps, the enterprises artificially reduce taxable income or shift profits to low tax jurisdictions in which little or no economic activity is performed.

For Example: A company ‘XYZ’ operating and earning revenue in India can show expenses related to another company situated in a tax-haven, thereby shifting its profit reducing overall taxable income in India. Most of these companies situated in tax havens are related to the parent company and are registered only to evade tax in the jurisdiction having higher rate of taxation. This leads to a huge erosion of taxes from the rightful government. Over the years India has particularly been a victim of such practices.

How is BEPS related to the Digital Economy?

With respect to digital economy the avenues for BEPS are manifold. Digitalization has provided new ways of mobility of intangibles suitable for tax evasion.

Companies can conduct substantial sales of goods and services in a market jurisdiction (suppose in the Indian market) from a remote location (suppose in Mauritius) through online platform. In such a manner by fragmenting the physical operations, the opportunities to achieve BEPS highly increase. Though the sales would be taking place in the Indian market, the profit would be generated in the Mauritius jurisdiction where it will generally be taxed at a meagre or nil rate, thereby helping companies to evade tax in India.

In such a scenario, it became pertinent for India to introduce taxation of digital services in order to safeguard its revenue.

Steps taken by India for taxing digital economy:

Digital market in India is growing at a rapid pace. Analyzing the online business scenario, internationally renowned financial services company Morgan Stanley has reported that the Indian e-commerce market is expected to grow to $200 billion by 2027. Therefore, India’s efforts for taxing the huge revenue being generated in its jurisdiction cannot be undermined.

India has strongly advocated source-based taxation with respect to the transactions being undertaken in the digital economy. Since, no consensus could be reached through the OECD platform for the time being, India went ahead and introduced digital tax in its jurisdiction independently.

The first such effort was taken in 2016, when India introduced an ‘EQUALISATION LEVY’ through The Finance Act 2016. The important point related to this levy are as follows:

- Equalization levy means the tax leviable on consideration (payment) received or receivable for certain specified digital services.

- The equalization levy was decided to be 6 per cent tax of the amount of the consideration

- The digital services on which these taxes were to be levied covered online advertising. It also includes any facility or service for the purpose of online advertisement.

- The tax would only be levied if the consideration is being received by a non-resident from:

- a person who is residing in India and carrying on business or profession; or

- a non-resident having a permanent establishment in India

In simpler terms, suppose Mr.X who is not a resident of India is providing services of online advertising either to Mr.Y who is residing in India and carrying on his business or to Mr.Z who is a foreign person having a permanent establishment in India, then whatever gross payment Mr.X would receive from the other two gentlemen would be taxed at 6% equalisation levy.

Thus, foreign persons or entities are the ones that would be subject to the digital tax, while Indian companies providing the same services would not be under the tax net.

As per law it was stated that it would be the responsibility of the recipient of the service (i.e. Mr. Y or Mr. Z) to deduct the equalisation levy from the amount paid or payable to a non-resident service provider of online advertising (i.e. Mr. X).

Several big companies like Google and Facebook had to pay increased taxes for the online advertising services they provided after the introduction of the equalization levy. This levy has also commonly been referred as ‘Google Tax’ as Google was the main company affected by this digital tax.

However, there were certain exemptions when the tax would not be charged, like:

- when the non-resident providing online advertising service (i.e. Mr. X) has a ‘permanent establishment’ in India and the provision of the service is connected with such permanent establishment;

- total amount received by Mr. X from Mr. Y or Mr. Z in a previous year does not exceed Rs. 1 lakh

In such cases, the provision of online advertisement would not attract the digital tax of 6%.

Enlargement of the scope of Equalisation Levy in 2020:

The Indian government brought in certain amendments to the provisions of the equalisation levy through The Finance Act 2020 and made them enforceable from 1st April 2020. These amendments introduced a new equalisation levy of 2 per cent on the amount received by an e-commerce operator from e-commerce supply of goods or service. This new equalisation levy has also been termed as the Digital Services Tax (DST).

Important points related to DST can be seen as follows:

1. DST applies to a broad range of service providers, but all the Indian companies are exempted from it.

2. The range of services provided by e-commerce operator that are subject to DST can be understood by going through the broad range of definition of e-commerce supply or services. It includes the following:

-

- online sale of good that are owned by the e-commerce operator; or

- online provision of services that are provided by the e-commerce operator; or

- online sale of goods or provision or services or both, that are ‘facilitated’ by the e-commerce operator

- any combination of activities of the above three clauses

- It can be seen that the definition is extremely broad and would mean that DST applies to revenue derived from nearly any type of digital activity that generates revenue in India

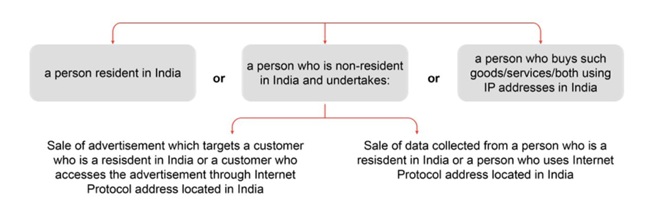

3. The DST shall be levied at 2% on consideration received by an e-commerce operator from e-commerce supply of goods or services made or provided or facilitated to:

- Thus, goods or services which are having a nexus with India are to be taxed with the DST.

4. Payment of the DST has to be made by the digital service provider to the Indian government. It means that the non-resident e-commerce operator is responsible for the deposition of the DST.

5. As per the current provisions, transactions entered into on or after April 1, 2021 which are chargeable to equalisation levy are exempt from income-tax.

6. The DST is a prospective tax, it would not be applicable in a retrospective manner.

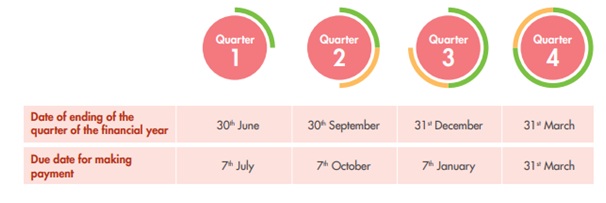

7. The digital service provider must pay the DST on a quarterly basis as per the following due dates:

8. There are three main cases when the DST would not apply:

- Non-resident e-commerce operators having a Permanent Establishment (‘PE’) in India and where the e-commerce transaction is effectively connected to such PE in India;

- Cases where the digital services company does not earn more than Rs. 2 Crores in India-based digital services revenue in the previous year;

- Where equalisation levy of 6% (the tax that was introduced in 2016) is applicable on provision of services of online advertising.

For example: If an Indian company pays Google to advertise on Google’s search engine, that revenue would be subject to 6% equalisation levy (digital advertising tax), here DST would not apply.

But if a foreign company pays Google to advertise to Indian users on Google’s search engine, that revenue would be subject to 2% DST.

Recently, the government has also clarified that there will be no digital tax if goods, services are sold via Indian arm of foreign e-commerce players.

Let’s have a look at the controversies related to India’s DST:

Since the introduction of these new provisions from April 2020, there have been several discussions regarding the scope and applicability of the equalisation levy/DST. Certain issues that have been highlighted with regard to this digital tax can be seen as follows:

1. It is alleged that the Indian DST discriminates against foreign entities and protects the Indian entities providing digital services.

- The government has refuted this allegation by stating that India based e-commerce operators are already paying taxes in India for the revenue they get from the Indian market, however, till now the e-commerce operators (not having any permanent Establishment in India) were not required to pay taxes for the consideration they received from the Indian digital market. In order to remove this discrepancy, the Equalisation Levy had to be introduced and is fully justified.

2. It is alleged that the Indian DST is extra-territorial as it is taxing foreign entities which are not under the control of the Indian government.

- It has been clarified by the government that Indian DST has no extra-territorial application since it is based on sales occurring in the Indian territory only through the digital means

- These entities earn huge revenue from their customer base in India, and thereby should be liable to be taxed

- Besides, the foreign digital businesses utilize the country’s infrastructure, stable economic and legal system and enjoy protection of their Intellectual property Rights as well in the country. Thus, taxing them is not an extra-territorial act.

3. It has been argued that DST is discriminatory because it targets only the digital services, but not similar services provided non-digitally.

- For example: If a non-resident company sells a movie to an Indian resident and delivers it online, the payment for such sale would be liable to DST. While if any other company sells the same movie to the customer in a DVD/CD, that sale would not be taxable under DST.

- Though, the situation given is correct, but the entire objective of DST is to regulate the digital economy, while for brick and mortar-based businesses the taxation principles are already well settled.

4. There are certain doubts regarding what actually constitutes a digital or electronic facility or platform.

- For example: If a non-resident Mr. X provides some advice to Mr. Y living in India on telephone or via email, will that also be considered as provision of services on the digital platform and thus liable to DST? There is lack of clarity about the ambit of DST in such cases.

5. The application of DST on the gross/entire amount of consideration received by the e-commerce operator from the customer has also led to creation of several doubts regarding the quantum of tax to be paid.

- For example: suppose an e-commerce operator – ABC, works on the ‘marketplace model’. Under such a model, ABC would only act as a link between the supplier and the customer, but it would be the one collecting payment from the customer for the goods/services supplied by the supplier.

- Now if ABC receives Rs.1000 as payment from the customer, out of this Rs. 990 is remitted to the supplier and Rs.10 is kept by ABC as a commission for its services. But since the gross amount received by ABC is Rs. 1000, as per law it would require to pay a DST of Rs. 20 (i.e. 2% of the total consideration). This tax is indeed is more than the commission that ABC would earn being an e-commerce operator!

- Therefore, there is need to clear such doubts and make the provisions of the law clearer.

6. Compliance burden for the foreign digital entities has increased post the introduction of DST.

As the payment of the DST has to be made by the digital service provider to the Indian government, they would require to get a PAN registration. For non-residents, obtaining a PAN number can be a time-consuming process.

7. The government has provided for Income Tax exemptions for the transactions coming under the scope of DST, but the date for applicability of this provision has raised some pertinent doubts of double taxation.

For example: While the DST applies with effect from April 1, 2020, the corresponding exemption from income tax in the hands of non-resident recipient applies only from April 1, 2021. Given the same, there could be a potential double whammy in Financial Year 2020-21, where the same transaction is subjected to equalisation levy as well as taxable in India as royalty or fees for technical services

8. As per the Integrated Goods and Services Tax (IGST) Act, online services provided by foreign entities to Indian customers would be liable to IGST as well. The digital businesses thus fear that they would be subjected to huge taxation burdens by paying both IGST and DST on the online services provided by them.

Apart from these major issues, there are certain other issues as well which are lingering as no detailed set of rules for implementing the DST have been released by the Government, thereby leading to the persistence of certain unanswerable questions.

Reaction of The USA to India’s DST:

The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) initiated an investigation of India’s 2020 Equalisation Levy (the DST) under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 of USA. Under the Section 301, US often investigates economic or trade practices which it perceives to be negative and if it indeed finds the practices to be discriminatory, it then imposes certain restrictions on the country from which such practices have originated.

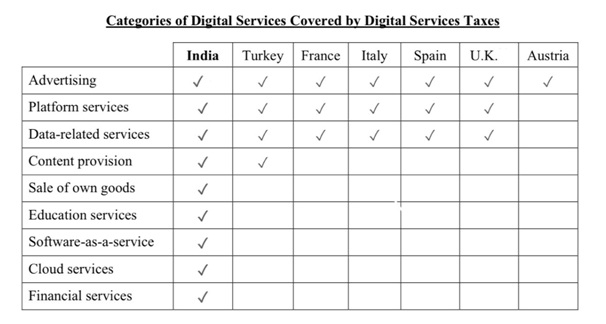

- It compared several other countries also which have introduced digital tax in their jurisdictions and concluded that India’s DST was very expansive, broad and included more taxes than other jurisdictions.

- The investigation concluded that India’s DST is discriminatory against U.S. companies, it contravenes prevailing international tax principles and is therefore unreasonable; andthus, India’s DST is actionable under Section 301.

- Under a similar case, the USTR had found France’s digital tax to be discriminatory too, and thereby US as an action imposed increased taxes on French goods being imported into the USA. Indian goods and services are also under the threat of similar retaliatory taxes being imposed following the report of the USTR.

- However, the Indian government has categorically rejected the findings of the USTR and stated that the Indian DST is non-discriminatory, at applies at par with all the digital entities under the ambit of the new law and therefore is not targeted against any US company.

- It is believed that USA has been acting in this manner as it fears that the many digital companies based in USA and earning huge revenue in the Indian digital market would be liable to pay the DST and therefore, the net income tax that they pay back in the USA would reduce. Because of the same reason, it is believed that USA has opposed digital tax being introduced by individual countries and also created roadblocks in the acceptance of a globally accepted solution through the OECD platform.

Conclusion:

- On the whole, it can be seen that the Indian Digital Service Tax/ Equalisation Levy is important to regulate the ever-growing digital market in the country. It is necessary to ensure that foreign entities earning revenue in India pay the proportionate amount of tax here, otherwise the domestic companies will be harmed due to skewed taxation policies. At the same time, the doubts relating to the newly introduced taxes have to be removed in a gradual manner by the government to provide continuity and clarity to the business ecosystem in India.

- The country has actively participated in the international efforts to frame guidelines for taxation of the emerging digital economy. Keeping in line with this principle, the further policies should also be formed within the overarching framework of the global consensus on this matter.