COVID-19 Compounds Global Challenges to Food Security

- The COVID-19 pandemic has had a massive impact on global food security and nutrition.

- However, before COVID-19, hundreds of millions of people were already suffering from hunger and malnutrition across the world.

Introduction

- The COVID-19 pandemic has had a massive impact on global food security and nutrition.

- However, before COVID-19, hundreds of millions of people were already suffering from hunger and malnutrition across the world.

- The pandemic and subsequent lockdown measures have only worsened the threat to food systems and possibly hastening the impending global food emergency.

- Besides pandemic, there are more grave threats such as political conflicts, natural disasters, and other events (locust swarms in developing regions).

This clears the picture that food insecurity is worsening and the world appears farther from meeting Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 2) on ‘Zero Hunger’. Thus, it becomes critical to analyse the current situation of food insecurity and how COVID-19 pandemic has worsen it.

What is Food Security?

- The World Food Summit of 1996 declared: “Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.”

- About 2 billion people were already at risk of moderate severe food insecurity, even before the pandemic.

- The government now faces difficulty to achieve the SDG 2 on the Estimated Year because of the pandemic.

Know Your Basics

|

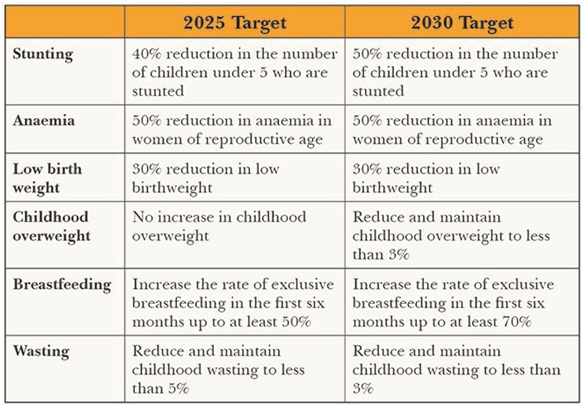

Global Nutrition Targets and SDG 2

|

Snapshot of ‘Undernourishment’

- Around 690 million people or 8.9 percent of the global population are undernourished.

- Asia is home to majority of the undernourished population (381 million)

- Africa has 250 million

- the Caribbean and Latin America follow (both with 48 million)

- In 2019, one in every ten people in the world (750 million) was facing severe food insecurity.

- Another 83 to 132 million are estimated to be added in 2020, bringing the number of undernourished to more than 840 million, or 10 percent of the population, by 2030.

- Off-track countries to achieve target: Many countries and regions are off-track to achieve the target of ‘zero hunger’:

- Africa will have half of all the world’s undernourished—433 million or 51.5 percent of the population—by 2030

- Asia will have 330 million (39.1 percent)

- Stunting has affected 149.2 million (22 percent) of all children under five years of age, as per Joint Malnutrition Estimate 2021.

- Wasting: continuously increasing at an alarming pace, wasting has reached an estimated 45.4 million (6.7 percent) of children in 2020.

- Overweight: In the incidence of overweight, there is the similar trend, with 38.9 million (5.7 percent) children affected in 2020.

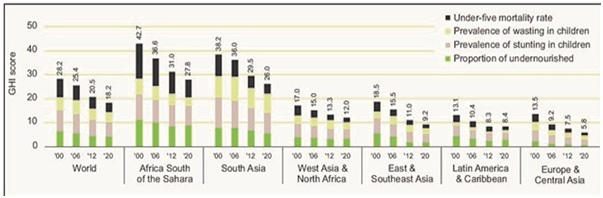

Global Hunger Index 2020

|

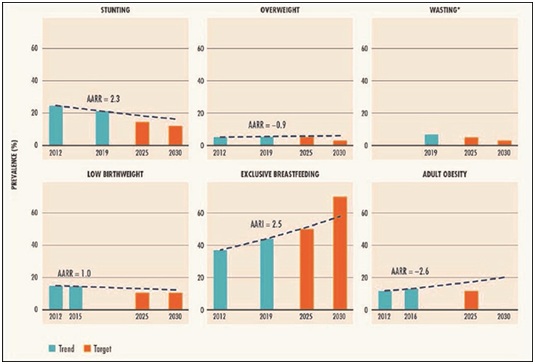

How is the world progressing towards meeting Global Nutrition Targets?

Stunting

- Stunting rates have reduced over the past two decades.

- However, certain regions continue to experience high rates of stunting, and the steepest numbers are in Asia (79 million) and Africa (61.4 million).

- Trend: There is a significant fall in stunting rates for Sub-Saharan Africa, due to antenatal care given to mothers and increased coverage of immunisation and deworming for children under-five.

- South Asia is the worst affected, with four out of every 10 children being stunted. Among the South Asian countries,

- Afghanistan has the highest prevalence at 41 percent

- India and Pakistan both at 38 percent

- Bangladesh and Nepal both at 36 percent

- In India, there is socio-economic disparity in the burden of malnutrition in households.

- Reasons: There are multiple factors that account for variance in child stunting rates:

- dietary diversity

- maternal education

- degree of household poverty

Wasting

- Globally, 45.4 million (6.7 percent) children under-five are wasted, far higher than the SDG-30 and Global Nutrition targets of 3 percent and 5 percent, respectively.

- South Asia accounts for 70 percent (31.9 million) of under-five wasting and more than a quarter (27 percent) live in Africa.

- Of the 31.9 million children affected by wasting in Asia, more than half live in South Asia (25 million).

Overweight

- The burden of overweight (in both under-fives and in adults) is continuously increasing.

- Globally, about 38.9 million (5.7 percent) of children under-five are overweight.

- Almost half of the total live in Asia (18.7 million)

- the other big proportion is in Africa (10.6 million)

Breastfeeding

- Of all other global targets, exclusive breastfeeding is the only indicator that appears to be on-track to achieve at least the 50-percent rate by 2025.

- At present, 44 percent of children are exclusively breastfed worldwide, with South Asia and East and Southern Africa above the global average at 57 percent and 56 percent, respectively.

Low birth rate

- Nearly 15 percent of infants born worldwide are of low birth weight (less than 2500 gm).

- Progress on the reduction of low birth weight has been stagnant for the past decades.

- South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America are the top three regions with the highest prevalence of low birth weight at 28, 13, and 9 percent, respectively.

- There has been slow progress in achieving the target of 30-percent reduction in low birth weight by 2030.

- Worldwide, about 13 percent of the adult populations are obese.

|

It is to be noted that overweight and obesity is the fifth leading cause of global deaths. |

How COVID-19 affects food security and nutrition?

- Multiple challenges: Lockdown and other containment measures have worsened

- loss of incomes

- disruption in food supply chain and social protection

- deepening inequality

- leading to uneven food prices

- Disrupted supply chain: Disrupted supply chain led to wastage, as demand dropped and farmers with inadequate storage were left with food they could not sell.

- Affected food production cycle: Travel restrictions affected the food production cycles that relied on migrant labour.

- Drop in purchasing power capability: Global economic recession led to loss of livelihood, causing a drop in purchasing power that in turn has resulted in food insecurity.

- Worsened inequalities: Economic slowdown worsened existing inequalities, and impacted food security.

- Increased likelihood of infection: One in every three people lacking access to safe drinking water and handwashing facilities. It increased the likelihood of contracting infections.

- Additional burden for women: Women faced additional burdens as frontline workers, unpaid care workers, and food system workers.

- Disruption of school meal program: The closure of schools led to disruption of the school meal porgramme. It affected the nutrition of some 370 million children.

- Altered overall food environment: COVID-19 has altered the ‘overall food environment’ as countries shut down informal food markets.

Overall impact of Covid-19

|

SDG 2 ‘Zero Hunger’: Why it Matters?

- Achieving ‘zero hunger’ is crucial for the world as it will have positive impacts on all sectors- health, economy, education, equality, and social development.

- To eradicate hunger, the SDG 2 targets need to be aligned to the four main dimensions of food security:

- food availability

- access to food

- food utilization

- overall stability of the three dimensions

Food Security: Challenges

- Challenges to food security:

- rapidly shifting food value chain and its impact on the diet of low- and middle-income countries

- urbanization

- move towards increased consumption of packaged foods

- Climate shocks and locust crises

- Barrier to SDG: Extreme hunger and malnutrition

What are the reasons for Prevailing Hunger?

- Poverty: Poverty and hunger, both exist in a vicious cycle.

- Food shortages: Various places in India have been repeatedly affected by food shortages and widespread malnutrition.

- Climate change: Too much or too little rainfall can destroy harvests or substantially reduce the amount of animal pasture available. Unfortunately, these fluctuations are likely to increase due to changes in climate.

|

The World Bank estimates that climate change has the power to push more than 100 million people into poverty over the next decade. |

- Poor nutrition: The less nutritious a person’s diet, the poorer their health will be, the less sustainable energy they will have, and the less likely they will be to break the poverty-hunger cycle.

- Poor policy implementation: Systemic problems (poor infrastructure or a lack of investment in agriculture), often make it hard for food and water to reach those who need it most.

- Bad state of economy: Much like the poverty-hunger cycle, nutritional resilience at a national level is tied to a country’s economic resilience.

- Gender inequality: In its outline of the SDGs, the United Nations (UN) reveals that “if women farmers had the same access to resources as men, the number of hungry in the world could be reduced by up to 150 million.”

- Female farmers are responsible for growing, harvesting, preparing, and selling the majority of food in poor countries.

- Women are on the frontlines of the fight against hunger. Still they are underrepresented at the forums where important decisions on policy and resources are made.

- Food wastage

Constitutional Provisions and Food Security:

|

How things can be improved?

- Focus on reducing cost of nutritious food: Nations must implement policies and channel investments for reducing the cost of nutritious food. The imperative is for policies and initiatives that will mainstream nutrition across all sectors, beyond health and agriculture.

- Robust food system: Working towards the global nutrition targets requires inclusive, sustainable and efficient food systems that deliver nutritious food.

- Easy access to poor: Urgent action is required to ensure access to the poorest of the poor.

- Nutrition-sensitive value chain: Policies need to be aligned towards a nutrition-sensitive value chain to enhance efficiencies in food storage, processing, packaging, distribution and marketing, thereby reducing food losses.

- Social protection programmes: To mitigate the societal disruption and economic shocks caused by the pandemic, more robust social protection programmes need to be initiated to improve access to healthy and nutritious food.

- Protection for vulnerable section: There should be better protections for vulnerable and marginalised food system workers and farmers who are disproportionately affected by the crisis.

- Focus on sustainable and economic growth: Sustainable and inclusive economic growth must be promoted to create more job opportunities and improve living standards.

- Women empowerment: Empowering women is key to improved nutrition, as they play a decisive role in their family’s food security.

Way forward

Despite progress made over the past few decades, the triple burden of undernutrition, obesity/overweight, and diet-related micronutrient deficiencies persist in many parts of the world. Ending hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition will require continued and focused efforts, especially in Asia and Africa—home to the largest populations that experience chronic hunger. Any progress in reducing undernutrition will have wide impacts on improving health and lifting people out of poverty.

The world needs a transformational change and collaborative work to develop strategies, cost-effective interventions and investments in nutrition. These are needed, along with poverty reduction, the empowerment of women, and improvements in maternal health.